The inefficiency, ineffectiveness, and apparent corruption led Congress to finally act on the matter in August 6, 1861 by creating a centralized Metropolitan Police District. Congress authorized the President to appoint five police commissioners; three from Washington, one from Georgetown and one from the part of the District of Columbia lying outside the city. The newly constituted Board of Police which also included the mayors of Washington and Georgetown, were directed to divide D.C. into ten precincts, establish police stations, and assign sergeants and patrolmen. The force's primary responsibilities were to render military assistance to the civil authorities, to quell riots, suppress insurrection, protect property, preserve the public tranquility, prevent crime and arrest offenders.

The Washington National Republican, an Administration mouthpiece, welcomed the appointment of new police commissioners and the creation of a metropolitan police force: "With the lights now before us, we believe the President has made a judicious selection and we look forward with confidence to the formation of a police system more perfect and efficient than is now enjoyed by any other city." The paper hoped that the Washington force would model itself after New York City's police department, which was considered the country's best and was itself modeled after London's famed Metropolitan police.

|

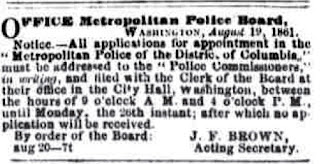

| August 24, 1861 Newspaper Ad for Policeman (LOC) |

Naturally, there was friction between the nascent police department and the military. Initially, the Provost Marshal refused to cooperate with the new department. On October 4, 1861, the President of the Board of Metropolitan Police wrote General George B. McClellan asking him to direct the Provost-Marshall to recognize the Metropolitan Police's supremacy on civil matters and to "cooperate with the civil police in all measures calculated to promote the tranquility of the city and best interests of the Government."

|

| William B. Webb, a local lawyer, served as the first Superintendent of the Washington Metropolitan Police from 1861-63. |

In October 1861, Patrolman Sebastian recorded the department's first arrest when he detained Charles Curtis for intoxication. With over 100,000 soldiers in and around the capital and the various vices that followed the army, there was a sharp increase in crime. It was estimated that there was not more than one policeman to every 1,000 persons in the city. Undermanned from the beginning, officers worked 12-hour shifts, seven days a week and received little to no time off. Most patrolled on foot, but there was a mounted component of about twenty patrolmen. Although there were some injuries, including an accidental shooting, the department would not lose an officer in the line of duty until 1871 when officer Francis M. Doyle was shot to death.

The Metropolitan Police kept careful records of criminal activity and even had a rudimentary system for tracking crime rates by precincts. From a glance at the department's 1863 report, we see that it recorded 23,912 arrests that year, about 4,000 of whom were females. 7,184 arrested that year were illiterate. The department claimed to have helped recover $86,000 in stolen property. Twelve patrolmen were assigned to patrol Pennsylvania Avenue from 1rst to 18th streets in an attempt to "protect ladies and others whilst crossing the streets," of the red-light district known as "Hooker's Division."

|

| Criminal offenses recorded by the Washington Metropolitan Police in 1863. (Report of the Secretary of Interior) |

In 1862, Congress authorized the Board of Police to hire six detectives and also charged the Superintendent with enforcing all public health ordinances, particularly those aimed at combating smallpox. Besides providing security during local elections, which had previously been marred by violence, the police also assisted in procuring the District's quota of troops for the draft.

The Metropolitan Police Responds to the Assassination of President Lincoln

On November 3, 1864, four Metropolitan Police officers were detailed to help protect the Executive Mansion and the President. However, the security afforded by this protection was relatively limited. Generally one officer accompanied Lincoln wherever he went, including his short strolls to the War Department to catch up on telegraph traffic. While such protection might deter a lone crank, it would not stop a committed assailant.

Presumably, only the fittest officers would be assigned to presidential duty. However, John Parker, an officer with a blotted record of multiple reprimands, including drinking on duty, was the guard who accompanied the Lincoln's to the theater on April 14, 1865. Parker showed up three hours late to begin his White House shift that afternoon. After the presidential party arrived at Ford's Theater, Parker was initially seated outside the president's box. However, since he could not get a good view of the play, he apparently abandoned his post for a better view of the stage. At intermission, he then went next door for drinks at the Star Saloon. At approximately 10 PM, when John Wilkes Booth approached the Presidential Box, Parker was not there to challenge him. Even if he had been manning his post, it is not certain that Parker would have prevented the well-known actor from entering the presidential box. However, another presidential bodyguard not on duty that night later blamed Parker for the assassination: "Had he [Parker] done his duty, I believe President Lincoln would not have been murdered.." Amazingly, Parker remained a Metropolitan Police office for another three years.

Major AC Richards, the then superintendent of the police, happened to be in the audience at Ford's Theater that fateful night and was soon directing investigatory efforts. In the hours immediately after the assassination, Metropolitan Police officers enforced closures of all places of entertainment and helped seal off the city. A tip provided to Metropolitan Police detectives indicated that the Surratt boarding house at 614 H Street was linked to the crime.

Sources

Cook, William H. Through Five Administrations: Reminiscences of Colonel William H.Cook. 1910.

Deeben, John. P. "To Protect and Serve, The Records of the D.C. Metropolitan Police, 1861-1930," Prologue Magazine, Spring 2008, Vol. 40, No.1.

"Maj A.C. Richards Dead," Washington Post, February 21, 1907.

Martin, Paul, "Lincoln's Missing Bodyguard," Smithsonian, April 8, 2010.

Sylvester, Richard. District of Columbia Police: A Retrospect of the Police Organizations of the Cities of Washington and Georgetown and the District of Columbia, with Biographical Sketches and Historic Cases, Washington, D.C.: Gibson Brothers, 1894.

Report of the Board of Metropolitan Police, Secretary of the Interior Report, Congressional Edition, 1864.

Steers, Edward. Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. University Press of Kentucky, 2001.

Tindall, William. Standard History of the City of Washington From a Study of the Original Sources. H.W. Crew & Co, 1914.

"National Capital Well Guarded City," Washington Evening Star, September 24, 1905.

"Washington Metropolitan Police," http://bytesofhistory.com/DCMPD/DCMPD_Menu.html

Washington National Republican, August 19, 1861

Willets, Gilson. Inside History of the White House. New York: The Christian Herald, 1908.

This is great stuff!

ReplyDelete150 years ago this week, to start 1862 off on the right foot, Washington's finest debuted new uniforms. The new uniforms were described with effusive praise in the December 31, 1861 edition of the Washington Evening Star: "The Metropolitan Police will appear in full uniform on the 1st of January. The cap is of blue cloth, of a very small pattern, and apparently well adapted to the service for which it is intended. The coast is of dark blue cloth, made as an over-coat, double-breasted, with two rows of handsome gilt buttons, upon which within a handsome wrought wreath appears the initial letter 'P' in the old English character. The coats for the sergeants and patrolmen differ only in the fact that upon the back skirt of the coast the former have six of these buttons, and the patrolmen have four. The pants are of the same colored cloth, with a neat white worsted coast in the sideseams. The staffs intended for use upon special occasions are similar in form to the one in common use, but are more handsomely turned, of rosewood and polished. The entire outfit is a very great improvement upon the uniform of the police.

ReplyDeleteWhere did your information come from Steven ?

ReplyDeletempdchistory1861@yahoo.com

I notify that this is the first place where I find issues I've been searching for. You have a clever yet attractive way of writing.

ReplyDeleteLogistics Service Provider Bangalore | Project Logistics Company | Logistics Services in Bangalore

Thanks for taking the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love learning more on this topic. If possible, as you gain expertise, would you mind updating your blog with more information? It is extremely helpful for me. Moss & Colella

ReplyDeleteThe inefficiency, ineffectiveness, and apparent corruption led Congress to finally act on the matter in August 6, 1861 by creating a centralized Metropolitan Police District. Congress authorized the President to appoint five police commissioners; three from Washington, one from Georgetown and one from the part of the District of Columbia lying outside the city

ReplyDeleteBlend Pedia

cricut design templates

cricut designs

cricut design

cricut valentine cards